|

| |||

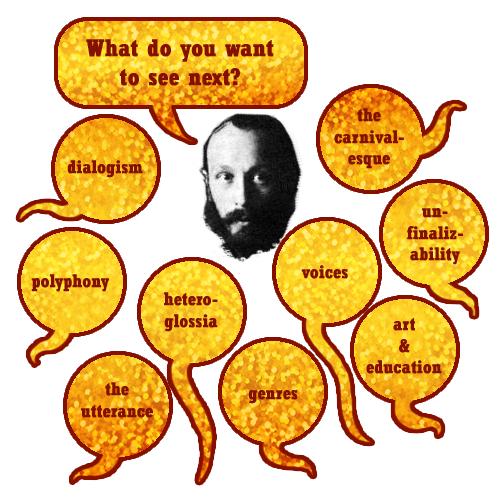

| Polyphony was a dialogic term Bakhtin used in his literary criticism, particularly with Dostoevsky. The word Polyphony is derived from a musical term which has special significance within the idiom of Russian Orthodoxy from which Bakhtin was operating. Here's an example of a traditionalist, monophonic Russian Orthodox chant: [You need Flash to listen to the MP3s] And here's an example of a later polyphonic Russian Orthodox chant: [You need Flash to listen to the MP3s] Note how in the monophonic chant, even when there are many singers, they sing in unison, in one voice, whereas in the polyphonic chant, the singers harmonize, singing in many voices. It's also notable that polyphonic chanting was an import from the West in the 17th century, and was heavily criticized by Russian traditionalists - not only its form, but its history is dialogic! |

||||

| ||||

Polyphony in Dostoevsky

Polyphony in Dostoevsky"Dostoevsky portrayed not the life of an idea in an isolated consciousness, and not the interrelationship of ideas, but the interaction of consciousnesses. . . . In Dostoevsky, consciousness never gravitates toward itself but is always found in intense relationship with another consciousness. Every experience, every thought of a character is internally dialogic, adorned with polemic, filled with struggle .... It could be said that Dostoevsky offers, in artistic form, something like a sociology of consciousness. " (Bakhtin, 1963/1984, p.32) |

||||

|

|

| |||

| So, Dostoevsky's characters had truly distinct voices, which interacted with each other in a dialogic way, independent of the voice of the author (Bakhtin, 1963/1984). But isn't that how novels work, the signature trait of the novelistic genre? Is there a counter-example? | ||||

| ||||

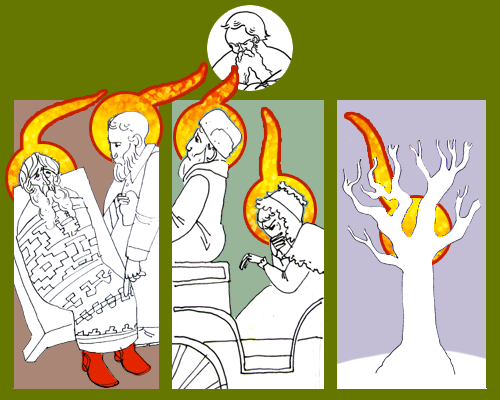

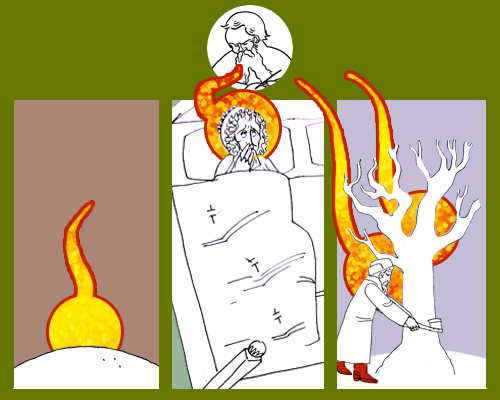

"We shall therefore analyze briefly, from the vantage point most relevant to

us, Leo Tolstoy's short story 'Three Deaths'. This work, not large in

size but nevertheless tri-leveled, is very characteristic of Tolstoy's monologic

manner.

"We shall therefore analyze briefly, from the vantage point most relevant to

us, Leo Tolstoy's short story 'Three Deaths'. This work, not large in

size but nevertheless tri-leveled, is very characteristic of Tolstoy's monologic

manner."Three deaths are portrayed in the story - the deaths of a rich noblewoman, a coachman, and a tree. But in this work Tolstoy presents death as a stage of life, as a stage illuminating that life, as the optimal point for understanding and evaluating that life in its entirety. Thus one could say that this story in fact portrays three lives totally finalized in their meaning and in their value. And in Tolstoy's story all three lives, and the levels defined by them, are internally self-enclosed and do not know one another. ... "Thus the total finalizing meaning of the life and death of each character is revealed only in the author's field of vision, and thanks solely to the advantageous 'surplus' which that field enjoys over every character, that is, thanks to that which the character cannot himself see or understand. This is the finalizing, monologic function of the author's 'surplus' field of vision." (Bakhtin, 1963/1984, p.95) |

||||

|

|

| |||

|

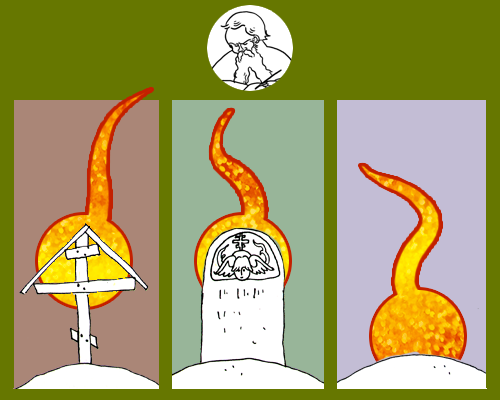

I think I get it. Tolstoy tends towards the didactic and the epic, and thus the monophonic. Let me see if I have this straight: The three deaths occur in three distinct 'panes' of the story, and the afflicted never dialogue with each other. The only connection between the three panes is a material exchange: the dying peasant gives his boots to the coachman of the dying woman, who cuts down the tree to mark the peasant's grave.  There is no sharing of consciousness. The woman doesn't in fact know that she is dying, and knows nothing of the death of the peasant or the tree. This knowledge is only reserved for the author, who takes a god-like omniscient role.  The deaths are all finalizing, both literally, and thematically. The characters themselves being dead, the death has no meaning for them. Their lives are summed up by this death for the benefit of the author (and reader), and their manner of death (the peasant quietly in the night in the rural roadhouse, the woman in confinement at her estate, lamenting leaving her husband and family behind for her health) are designed to be instructive to us, rather than the characters. The three deaths illuminate each other, but only for the author, in his privileged vantagepoint.  How would Dostoevsky do this differently? |

||||

| ||||

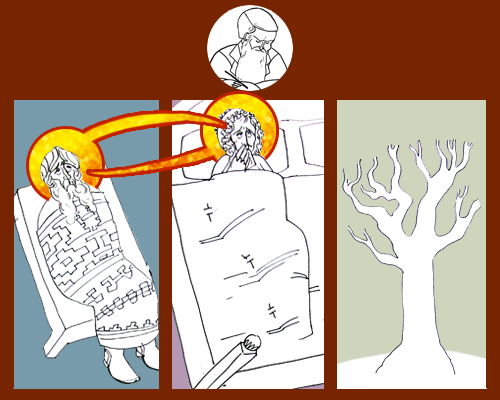

| How would 'Three Deaths' look if (and let us

permit ourselves for a moment this strange assumption) Dostoevsky had

written them, that is, if they had been structured in a polyphonic manner? He would have introduced the life and death of the coachman and the tree into the field of vision and consciousness of the noblewoman, and the noblewoman's life into the field of vision and consciousness of the coachman. He would have forced his characters to see and know all those essential things that he himself - the author - sees and knows. He would not have retained for himself any essential authorial 'surplus' (essential, that is, from the point of view of the desired truth). He would have arranged a face-to- face confrontation between the truth of the noblewoman and the truth of the coachman, and he would have forced them to come into dialogic contact. (Bakhtin, 1963/1984, p.95) And in the words of the story not only the pure intonations of the author would be heard, but also the intonations of the noblewoman and the coachman; that is, words would be double-voiced, in each word an argument (a microdialogue) would ring out, and there could be heard echoes of the great dialogue. ... Of course Dostoevsky would never have depicted three deaths: in his world, where self-consciousness is the dominant of a person's image and where the interaction of full and autonomous consciousnesses is the fundamental event, death cannot function as something that finalizes and elucidates life. (Bakhtin, 1963/1984, p.95) |

||||

|

|

| |||

|

So, (pursuing this "strange assumption," and acknowledging that neither of us are Dostoevsky), it may be structured more like this: The woman, suffering with consumption, would come face to face with the peasant suffering from consumption (perhaps impatient with her coachman who she discovers is trying to needle a dying peasant out of his boots). Their fates would become known to each other, and perhaps they may even exchange words in the idiom of their respective social classes.  After the woman heads abroad for her confinement her encounter with the peasant remains in her consciousness. Even if she doesn't explicitly acknowledge it, the shared fate of the characters is leant a dialogic weight and meaning by their mutual knowledge of each others' conditions. The characters may recover, or may not, but within the story they will not simply die - more likely it would end at a threshold - perhaps the woman's preparation to return hom after recovery. The ultimate fate of the characters would be as unknown to the reader and author as to them, as they are on an equal, dialogic, level within the work.  |

||||

Ayers, W., & Alexander-Tanner, R. (2010). To teach: The journey, in comics. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). Discourse in the novel (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). In M. Holquist (Ed.), The dialogic imagination: Four essays by Mikhail Bakhtin (pp. 259-422). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. (Original work published 1975).

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). Epic and Novel (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). In M. Holquist (Ed.), The dialogic imagination: Four essays by Mikhail Bakhtin (pp. 3-40). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. (Original work published 1941).

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). Forms of time and of the chronotope in the novel (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). In M. Holquist (Ed.), The dialogic imagination: Four essays by Mikhail Bakhtin (pp. 84-258). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. (Original work published 1937).

Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). From Rabelais and his world (H. lswolsky, Trans.). In P. Morris (Ed.), The Bakhtin reader (pp. 195-244). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1965).

Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). Problems of dostoevsky's poetics. (C. Emerson, Trans.). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published in 1963).

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). From speech genres and other late essays (H. lswolsky, Trans.). In P. Morris (Ed.), The Bakhtin reader (pp. 81-87). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1976).

Cuenca, A. (2010). Democratic means for democratic ends: The possibilities of Bakhtin's dialogic pedagogy for social studies. The Social Studies, 102(1), 42-48.

Dimitriadis, G., & Kamberelis, G. (2006). Theory for education. New York, NY: Routledge.

Miles, A. P. (2010). Dialogic encounters as art education. Studies in art education: A journal of issues and research 51(4), 375-379.

Roberts, G. (1994). A glossary of key terms. In P. Morris (Ed.), The Bakhtin reader (pp. 245-252). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Rule, P. (2011). Bakhtin and Freire: Dialogue, dialectic and boundary learning. Educational philosophy and theory 43(9), 924-942.